Resources

Author: Tom Novosel Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3

Hydro-electric development proves a worthy example in regards to a lack of regional control of development. Water as a resource provides power generation, irrigation, domestic water supply, flood control, recreation, and navigation. But conflicts can arise over hydro-electric development, which not only effects fish preservation and other recreational uses, but also floods land that indigenous peoples have used for traditional hunting and trapping purposes. Other industrial developments also give rise to issues of pollution, which effects both wildlife and inhabitants. Although multi-purpose planning is strived for, resource development initiatives have not always incorporated Native and northern perspectives; the country’s northern regions are never totally uninhabited. Yet, personal letters to the prime minister, such as this one to Diefenbaker in 1960 from Mark M. de Weerdt, a lawyer from Yellowknife, further complicates the issue when he writes: “Those of us who have settled in the North may be few in number but we trust that we may be counted among those who see a greater future for Canada in the difficult times ahead not through neglect of her sleeping strength, but by its development.”

For many years, then, the northern regions themselves did not warrant any special attention in the Canadian and North American social fabric other than as a “vast unoccupied continent [where] the development of unlimited resources” should be exploited, as one American railroad company suggests. While the majority of northern regions have been underdeveloped, what remained unconsidered for the majority of the time was the impact of resource development upon northern lands, wildlife, and the north’s local inhabitants, particularly its Indigenous peoples in those areas that were being developed.

Indian peoples of the north, such as the Dene in the sub-Arctic region to the many bands throughout the Yukon and Northwest Territories and Nunavut today, to the Inuit all across the Arctic region, have lived in these northern regions for thousands of years. They have relied on and lived off the land and wildlife by traditional hunting and trapping techniques for food, clothing, and shelter. In other words, northern resources are more than just about economic development; they are also about sustaining a livelihood, family, community, and culture.

The history of the fur-trade, involving the Hudson’s Bay Company, Northwest Company, and Indians from all across the northern region of the continent, was also relevant for the Inuit in the Arctic. For example, the Inuit were involved in the early whaling industry with European explorers. What is most important to understand is that traditional trading, trapping, and hunting continued well into the twentieth century. Resources utilized for food consumption, such as fish, caribou, and sea mammals, for both the people and sled dogs have allowed for their continued subsistence.

As the 1900s wore on, Indians and Inuit became more and more included in the Canadian economy. Other than industries and governments employing Indians and Inuit during northern resource development ventures, ranging from working in mines and on oil rigs to all aspects of the forest industry, they also learned ways to sustain their own traditional lifestyles. Entering into co-operative practices is one example of Indigenous peoples using commercial business techniques for economic development of northern communities and continuing to trade with, and supporting the local Hudson’s Bay Company stores further allowed their voices to be heard.

While food resources have not traditionally been a problem for all northern inhabitants, resource development has at times caused alarm regarding issues concerning wildlife, the environment, and conservation. Concern for the environment has always existed somewhat in certain areas across Canada, mostly noticeable in the creation of national and provincial parks; where, for example, Canadians and tourists have enjoyed recreational use of the wildlife, by sport hunting, land and water. Crown lands, which governments have historically held to either control economic development of certain industries such as forestry or to help sustain Indian peoples’ traditional trapping and hunting lifestyle, have also kept environmental and conservation issues on the table. Yet the federal government and private industry have fluctuated between both succeeding and failing at times when considering now to balance these issues. Historian Morris Zaslow states, “as the vehemence of the archivist onslaught grew, governments found it increasingly difficult to promote natural resource development.”

As early as 1909-1921 a federal body known as the Conservation Commission existed. However, environmentalism and conservation have had different meanings throughout the twentieth century. The “Resources for Tomorrow Conference” held in Montreal October 23-28, 1961, explains some of the ways in which government and industry have dealt with these issues. The idea of the conference was to facilitate cooperation between federal, provincial, and municipal governments, as well as private industry to help understand their respective roles in the national development program. Some participants stated that “We are only rich in our resources to the extent that we can turn them into income and employment opportunities” and that “Renewable resources are not meant to be preserved for the sake of preservation.”

The thrust, then, was to somehow reach a compromise that did not protect and lock up resources, but on how to improve the use of resources for future generations, all within the framework of economic development. Essentially the thrust was on renewable resources, such as forests. Conservation, planning, and development of renewable resources were focused on how to best utilize them, replacing and replenishing them, as in reforestation, in order to sustain future growth in the economy. Government and industry were not yet as interested in conserving the environment as an aesthetic beauty, since there was too much wealth to be made. Furthermore, some of the obstacles to overcome in resource development began to be technical, requiring new machinery and equipment the farther north one went; administrative, whether federal or provincial jurisdictions superseded in resource management in certain regions, such as off-shore oil exploration; and legal, especially with the rise of Indian land claims.

Well into the 1970s it was clear there were no easy answers to reconciling resource development and the environment. Years of ignorance and carelessness caused massive damage through flooding and chemical pollution of soils, waters, and the air. In regards to Native land claims and environmental disturbance to lands susceptible to damage by surface use, former Northern Affairs Minister Judd Buchanan stated on May 19, 1976: “I recognize the national need to know Canada’s true oil and gas reserves as soon as possible and I share with my colleagues the responsibility to implement [any] new legislation [and existing ones such as the Northern Inland Waters Act, the Territorial Lands Act and the Arctic Waters Pollution Act Prevention Act, on exploration, but] on the other hand, I also share with many northerners – particularly the Indian, Inuit and Métis people – their concerns for possible undesirable effects increased development activity may have on the environment and the people. The native people are the biggest users of the land, animals, fish and sea mammals.”

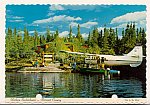

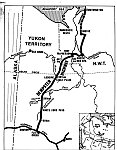

The construction of the Dempster Highway, beginning in 1959 as part of the roads to resources program, gives another and final very relevant example on how difficult it has been to compromise development with northern resource issues. Air and water transportation, other than a winter road, are still the only available means to travel to Tuktoyaktuk, Northwest Territories. Today the Dempster Highway concludes in Inuvik, but when it opened in 1979 when plans still existed to extend the highway further “no one [knew] for sure the impact the project [would] have on the native population, the economy, the land and the wildlife, including a herd of 100,000 caribou that regularly migrates across the highway’s route.” What we saw here, and continue seeing today are further negotiations on how best to compromise the issues of resource development when there are clearly many different actors involved. Historian Morris Zaslow concludes that “well-meant but tragically inadequate efforts were being made to protect native inhabitants and wildlife from the worst effects of the invasion of their homelands and to help the peoples adapt as painlessly as possible to the requirements of the changing times.”

Resources then have meant many different things to the people of Canada, especially to those residing in the country’s vast southern and northern regions. For those who live in the southern portions of Canada, typically close to the 49th parallel, northern resources development has helped build a strong and vibrant Canadian economy. We only have to look at the many pulp and paper mills, mines, hydro-electric dams, and oil wells dotted across Canada that induced industrial development and sustains our manufacturing sector in the south. As the Diefenbaker government stated in its paper “The Role the North Should Play in Canadian Development”, “the North is our ace in the hole. It is our economic future.” No doubt many still abide by this principle.

Modern transportation routes have made the country’s far northern resources more accessible, and therefore more readily available for development. While older northern communities have received a boost in their economies through resources development, newer ones have also come into existence. Another spin-off of resource development is the tourist industry, typically in national and provincial parks in the northern regions, where environmentalism and conservation issues regarding land and water use and wildlife are at the forefront. Not only have Canada’s Indigenous peoples been concerned with the environment and conservation regarding their traditional lifestyle, but interest groups and the federal and provincial governments have expressed concern when considering the country’s future and resources.

Sometimes there is a fine line between resource exploitation and economic resource development. Canada’s northern resource revenue has traditionally flowed into the southern heartland; if this wealth can further help our northern region’s economic, political, and social development, then we will know Canada is beginning to incorporate a more meaningful, balanced northern strategy. Canada’s natural resources are found in remote, neglected, but often accessible northern regions, and most of all continue to pose challenges and opportunities to our country’s national and northern planning and development.