Art and Artists

Author: Tom Novosel Page 1 | Page 2 | Page 3

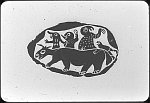

First Nations peoples have not only used totem poles as a means of storytelling, but also pictographs; another form of cultural and spiritual artefacts. Pictographs are rock paintings made usually with the finger in red ochre. Pictographs are in existence that are several thousands of years old, although there is no precise way to date them. Many are found in the provincial norths and boreal forest regions of Canada, and not really in the northern lands of the Arctic. Like totem poles, pictographs are more an expression of Native artwork and not Inuit.

One of the keys to trying to understand pictographs is symbol interpretation; they can sometimes be indecipherable. Some pictographs are believed to be linked to shamanism, which is a widespread religious tradition in which the shaman’s major tasks are healing, prophesy, or searching for helping spirits; the shaman has been an important aspect to many Native histories. But many First Nations also consider pictographs to be sacred in other ways as their cultures emphasize that they can be visions or spirit quests or dreams painted on the rock. The images or symbols depicted in pictographs were sometimes also meant to act like maps illustrating directions and distance to a watering-hole or where an abundance of game could be found, for example. Because many pictographs lie on rocks at the edges of rivers or in open territories and are sometimes clearly visible, they have become susceptible to vandalism such as spray painting or have been negatively impacted by landscaping and dam or highway construction.

Inuksuit are also one of the most lasting and enduring powerful traditional symbols of Inuit culture still visible today all across the vast Arctic tundra. An Inuksuk is a stone structure that today most resembles a human, although the Inuit history of building Inuksuit has seen them resemble many different shapes of whatever the artist intends; however, the primary purpose of an Inuksuk has always been to communicate knowledge from one human to another. Because stones themselves are a piece of the earth and rocks are a prominent symbol of Arctic lands, Inuit culture has embraced stones as material that the earth has offered as an instrument of expression, using them to express their close connection and harmony with the land and balance between people and nature. An Inuksuk is a symbol of respect if erected as a memorial to a loved one, a symbol of appreciation if meant to show the magnificence of the land, or even a symbol of honour in places that have had great spiritual significance to the Inuit.

Inuksuit act in the place of messengers, and can be stacked in order to communicate knowledge about the land, but its meaning depends on the intent of the person who builds it. When found in the Arctic an Inuksuk is usually sitting on elevated ground in order for it to be seen from a distance visible as a silhouette against the snowy landscape, glistening seashore, or vast Arctic sky. An Inuksuk’s position is selected specifically for it to withstand cruel winds and weather, and is also meant to reflect its meaning. Inuksuit can act like signposts, directional or navigational markers showing the correct and safest trail for those who are journeying across northern lands or simply suggest a good hunting or fishing place. Some more modern Inuksuit might be placed in gardens signifying peace and beauty or at a picnic spot signifying a place of plenty; these are said to be made for recreational purposes. One of the most traditional places for an Inuksuk might see artists erecting it near the entrance to their home or community as a sign of welcome and intended communication, even suggesting support, caring, and sharing. Inuksuit embody the spirits of strength and hope, and according to Inuit tradition they are sacred and should never be destroyed.

While the igloo itself is not really viewed as a form of artistic expression, it has been a survival mechanism and one of the most known cultural markers for the Inuit people and of the Canadian Arctic north as a whole. Mostly made during the winter season, Inuit have traditionally built igloos with the use of blocks of ice, snow, or materials such as whale ribs or driftwood reinforced with snow. During the summer months, many Inuit live in tents made of animal skins, called haumuq. Knowing how to either construct a proper igloo or pitch a tent meant to withstand blizzards, blowing snow, rain, or wind are good examples of northern knowledge that indigenous peoples of the north are usually expected to know and pass down through generations; this, then, could be seen as teaching a specific art form.

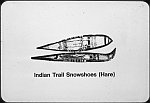

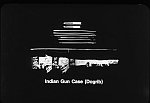

Not only have the land and water been important to First Nations and Inuit peoples, but also animals and all of their parts, of which indigenous peoples have almost always made use after a hunt. For example, seals and caribou have provided meat for food, but their skins have been used for making traditional clothing, blankets, tents, and boats; bones for making tools; intestines for making rain gear; and sinews used for sewing thread. Furthermore, First Nations and Inuit peoples make kayaks with sealskin or caribou skin over sturdy, lightweight wooden frames. All of the aforementioned traits, then, can be seen as indigenous peoples’ earliest efforts of artistic expressions; but the hunt itself, involving the peoples and animals, has been an overarching inspiration for many artists’ subsequent works of art. It is quite evident that artists have much respect for the animals which they represent in their artwork, just as their cultures respect the need to fully utilize the whole animal after a hunt.

Inuit art sometimes depicts the artist’s dreams. Many Inuit traditionally believed that dreams contained useful information for hunting and daily life. Storytelling is a traditional form of art in Inuit culture, and artists have created works of art that display the artist’s perception of a story. In Inuit myths and legends, animals often have special powers, such as the ability to change into human beings or the ability to speak. And just as there are many versions of a single myth, sometimes a work of art can have several different interpretations. Overall it is almost impossible to know the objectives of the ancient Inuit artists, since no written record accompanies their work; today’s artists, however, allow some interpretations to become known. One of the best ways to begin a tour of Inuit art is by taking a stroll through an Arts and Craft shop such as the one in existence at Rankin Inlet, Nunavut (formerly Northwest Territories).

The subject matter of Inuit sculptures, carvings, print, and drawings largely portrays animals, family life, hunting, legends, and even shamans – spiritual leaders believed to have supernatural powers, including the ability to communicate with the spirit world. It seems that humans tend to be at the centre of most works of Inuit art, though, since they could offer the most in subject matter as the lives of people are infinitely better understood than the lives of animals. The Inuit do not have a directly translated word for art, but rather the word used is sananquaq, which means “making a likeness”; this might speak to Inuit art being characterized by simplicity and strength, with their statements being direct and vivid. Sananquaq also speaks to the way in which Inuit art is largely representational and not abstract, perhaps meaning that when the artist chooses to depict animals, for example, it is because they carry significance in reality and in representation. Although artwork might have a spiritual or folklore dimension which the audience might not know from viewing the work, they are usually aware they are viewing an animal or person, for example.

Inuit sculptures and stone carvings that are of animals and people tend to have a lifelike vitality. Because these works of art are three-dimensional, giving height, width, and depth, form and shape are most important. The Inuit mostly use materials only found in the Arctic. The traditional sculpture and stone carving making came from hand carving the tools, weapons, and utensils necessary for hunting, fishing, cooking, and shelter building. Today’s materials include a variety of local stones, as well as many animal substances such as whalebone, caribou antler, musk ox horn, and walrus tusk. The use of materials from their environment shows a level of intimacy with their subject matter.

As they come from a hunter society, the Inuit’s artistic eye is trained to be sensitive and to observe very closely. Because the Inuit have historically depended on animals for survival, which speaks to the importance of wildlife to traditional Inuit culture, those who have hunted animals became keen observers of them in the wild; this holds true for the artist as well, as it holds that the artist is a hunter first. It is important for the Inuit artist to capture and re-create an animal’s shape, gesture, pose, and expression in works of sculpture or carving. The artist muse relate an attitude of respect and admiration for the animal and it is hoped the audience also holds a certain reverence for the subject of the sculpture or carving as the artist sensitively portrays the animal’s strength and beauty. Print carvings of owls, with a large wingspan, or polar bears on their hind legs speak to this powerful sentiment.