Imagining Animals

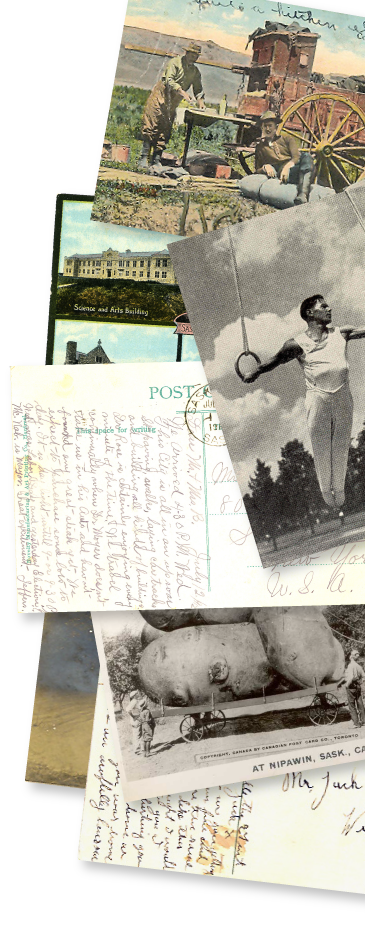

The Illustrated Postcards of the Mary Taylor Postcard Collection

Author: Alison Cooley

Images of animals abound in mass culture. In current-day print and digital media, images of animals are powerful ideological metaphors, diverse in scope and subject matter. Contemporary nature photography allies itself with ecological concerns, but also replicates the ritual of hunting (now done out of sport rather than necessity), with the camera.1 And while technology has influenced the means of production of the image of the animal, the frameworks that govern the production of the nature image are deeply rooted in our culture and history. A closer examination of animal illustrations in the Mary Taylor Postcard Collection reveals the early 20th century views of the animal, and its symbolic uses within the shifting contexts of British and Canadian culture.

In his influential 1980 essay, “Why Look at Animals?” John Berger wrote that the proliferation of the animal image is a symptom of the change in relationships between humans and nature that arose during the industrial revolution. According to Berger, all images of animals, from those of the nature photograph, to those in the talking animal stories of Disney cartoons, are part the visual compensation for the animal's disappearance from larger society. “The animals of the mind,” he writes, “instead of being dispersed, have been co-opted into other categories so that the category animals has lost its central importance. Mostly they have been co-opted into the family and into the spectacle.”2 The images of animals in Mary Taylor's postcard collection are, like modern-day popular images of animals, representations of this kind of co-option. They place animals in the particular space of being both objects of familial affection and signifiers of the exotic and sublime.

The 19th century epitomized changing relationships between humans and animals. Carolus Linnaeus's taxonomic classification system for animal species, established in the 18th century with the publication of Systema Naturae (1735), and Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species (1859), fostered new ways of understanding human and non-human animals. Taxonomic classification allowed Victorians to see humans and animals as both separate and alike. Victorians saw similarities between animals and the original inhabitants of the British colonies in their apparent “savageness.” This comparison provided justification for imperialism and furthered the interests of British colonists through ethnographic documentation3. And yet, in their extreme difference, animals provided a metaphor for an exotic, fanciful nature on the periphery of society. As documented by a number of theorists, the emergence of the zoo as an attraction,4 and the selective breeding of hybrid animals for novelty purposes5 solidified this ideal in English society. So as the 19th century understanding of animals became much more complex and nuanced, this understanding manifested itself in fairly diverse (albeit often surprisingly simplistic) ways. Many of these attitudes (and their manifestations) bled over into the 20th century, remaining as tropes in the visual rhetoric of mass culture.

Images like “The Swan's Retreat” (figure 1) use the gaze to establish the human link with nature. Unlike most nature photography, which features spectacular views of the animal in its natural habitat, these illustrated images are dominated by the human subject. Human presence in the image (through costume, gesture, and context) prevents us from seeing nature as timeless or ahistorical.6 In this image the woman and child, by virtue of scale and composition, read as the primary subjects. They fabricate an encounter with the animal that allows the viewer to occupy the wilderness scene. As viewers, we are witness to the gaze taking place in the human-animal encounter, but we are also granted the ability to hold the animal's gaze by assuming the role of “human.” The viewer is not merely a casual observer, but rather a participant in the experience of nature.

However, as revealed by their costume, the mother and child do not abandon British high society in favour of a savage nature. Rather, they participate in its domestication. In this particular image, the link between human and animal is specifically feminine, and specifically child-like. The maternal element of child and guardian is mirrored throughout this scene, in the child's care for the kitten, and the adult's supervision of the child. Indeed, in the symbolism of the bird (here a swan) as an egg-laying and nest-making creature, the notion of parent and guardian repeats. These roles are purely symbolic, however. Animal consciousness does not factor into the encounter. Rather the animals are appropriated as part of the visual rhetoric, or, as Berger would have it, co-opted, in this case as family.

Generally, the image of nature in Victorian society is “about the mood evoked by the picturesque more than it is about any particular event within it.”7 The boat, the swan, the human figures -- each exists as an atmospheric element, contributing to the vision of nature as a “repository of feeling” 8 removed from, but tangent to, society and the domestic.9 In this case, the kitten the young girl holds becomes merely a prop; a motif necessary for the young girl's play at maternity, rather than an entity unto itself. In this over-sweet interaction, the child demonstrates an element of care and stewardship of nature. Additionally, in allying femininized domesticity with the animal, the image further presents a system of cultural control. Positioning women, children, and animals as parallel does not break the hierarchy of “man over nature” present in the Victorian era. Rather, it legitimizes it by producing ties between views of the feminine in Victorian society—as “natural” (rather than logical), unobtrusive, and beautiful--and the imagined roles of animals. Maternal roles, specifically, solidify the bonds between women, children, and animals.

In an image entitled “A Doubtful Acquaintance” (figure 2), a bird again appeals to the maternal instinct. This symbolism is fairly common in the Mary Taylor collection. Birds were for some time extremely popular images in the greeting and postcard industry of the 19th century,10 and so it is not surprising that they appear so frequently in this collection. The question of the bird's significance, however, is much more interesting.

In this image, the tentative and somewhat anxious interaction between the child and the mother duck is akin to an encounter with a stranger. In this image, the human figure dominates the encounter to a much lesser extent than in figure 1. In fact, the child figure is even made vulnerable by the animal’s actions. Here, however, the sweetness and pleasure lies in the viewer’s knowledge that the stranger is both harmless and mildly absurd in its behaviour. Adult knowledge of the animal ‘other,’ recognized as both gentle and symbolic, allows the viewer to dominate the encounter regardless of the child's aversion. The viewer therefore dismisses any tension between human and animal in this encounter.

While these images are mechanisms of delight and sentiment, they still contain within them the intrinsic assumption of human domination over nature. These images of animals as domestic figures allow the viewer to fabricate an understanding of the animal and its relationship to humans, without actually encountering animals. Postcards of animals, like other mass-produced depictions, compensate for the relegation of actual animals to the periphery of society. Therefore, these images are emblematic of the animal’s changing role in an industrial age, in which both animal and human are replaced by advances in technology. Despite the fascination with the animal encounter and the apparent beauty of that encounter, these birds occupy only a metaphorical space. The relationships between human and animal depicted in the postcards are merely figments of the imagination. Thus, the images’ attempts to relate animal to human, to anthropomorphize, and to allow the viewer entrance into the scenario, manufacture a consumable animal fantasy.

Even more clearly, postcards of the fox hunt (figure 3, “A Good Start) also depict humans asserting themselves over nature. In these images, this dominance is more pronounced, and while it is still an upper class British dominance, its expressions are not entirely domestic. This dominance comes in the form of animal labour -- the horses and hounds are, again, props to the activity of the hunt. Further, they are, like the mother duck, mechanisms for the evocation of human emotion. The dogs convey enthusiasm for the chase, emphasizing by their dynamic pose the speed and excitement of the pursuit. In their physical proximity to the woman, rather than to the other figure in the distance, they express a different kind of familial connection from those seen in the bird images. The dogs, in this image, are not merely tools used to accomplish the task of the hunt; they also play at a companionship. They belong to the human subject, rather than dominate the hunt as they might realistically do. Like the birds, they also play-act at humanity. Unlike the birds, however, the dogs are already domesticated for a particular purpose, and so this image represents not just a fantasy of domestication, but its reality.

For Mary Taylor, a native of Sheffield England, who immigrated to Canada in 1912, these postcards represented a larger nostalgia for home.11 In these images, the fox hunt itself may read as a symbol of Britishness—a memory of a classed and culturally specific practice absent from Taylor’s new Canadian life. While Taylor's lifestyle near Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan was likely typical of the early settlers, her postcard album reflected instead the upper-class British lifestyle of the late 19th and early 20th centuries—a lifestyle she likely was not a part of, even in Sheffield. Nowhere in Taylor's postcard collection are the labouring livestock of the Canadian prairies in the days of early settlement. Nor is the necessity of animal-as-food reconstructed for the viewer. And while these may seem unlikely postcard narratives, they are in fact clearly articulated in many of the contemporary postcards produced in the Canadian west.

The images in figures 4 and 5 (both from the Canadiana Pamphlets collection), are the kind of images that contrast with those in Mary Taylor's collection. In the image of the “Calgary Bucker,” there is a tension between human and animal; a heroism in man's dominance over nature, but not without signs of a struggle. Whereas the image of members of the Blackfoot First Nations on horses (Figure 7) present the heroism of the exotic. This is an image of “primitive” man's oneness with nature. The images in Mary Taylor's collection are entirely unlike these images. The nature they present is a thoroughly domestic and domesticated one; a nature made consumable and collectable by the reduction of tension between human and animal.

Therein lies the power of the mass production and distribution of illustration. The illustrated postcard, with its ability to perpetuate pretty, nostalgic, fantastical constructions, held powerful sway in a society shifting towards photography. As photography became a more commonplace practice in the mass-production of images, the kinds of available representations of nature changed. Photographers in the early 1900's were unable, for technical reasons, to produce accurate or even seemingly accurate images of nature12. In other words; photography was incapable of suspending disbelief in the human-animal encounter. The images in the Taylor postcard collection maintain a Victorian understanding of nature and the animal, and function as nostalgic tokens of an idealized time and place. The animals’ encounters with humans act as sentimental remembrances of domesticated Victorian English culture. The images in the Mary Taylor postcard collection represent, therefore, two layers of nostalgia: one for a wistful recollection of homeland, and the other a longing for a society that had arguably never existed during Taylor's lifetime -- a society at one with nature.

Notes

1 Brower, Matthew. “Take Only Photographs: Animal Photography's Construction of Nature Love.” Invisible Culture: An Electronic Journal for Visual Culture. Issue 9 (2005): http://www.rochester.edu/in_visible_culture/Issue_9/brower.html

2 Berger, John. “Why Look at Animals?” About Looking. New York: Pantheon, 1990. 1-26. Print. Pg 13.

3 Ritvo, Harriet. “Our Animal Cousins.” Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, Spring2004, Vol. 15 Issue 1, p48-68, 21p. Academic Search Complete. Web. 23 February, 2010. Pg. 50

4 Berger, 18.

5 Ritvo, 53.

6 Brower

7 Brower.

8 Brower.

9 Knoepflmacher, U.C, and Tennyson, G.B.“Introduction.” Nature and the Victorian Imagination. Knoepflmacher and Tennyson, eds. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1977., xxi.

10 Watkins, David. “Victorians' festive fowl.” Poultry World, Dec 2005, Vol. 159 Issue 12, p23.

11 University of Saskatchewan Archives, Mary Taylor Postcard Collection, MG 296. Finding aid: fonds-level description.

12 Brower

Works Cited

Aslam, Dilpazier. “Ten Things you Didn't Know About Hunting With Hounds.” Guardian.co.uk. 18 February, 2005.

Berger, John. “Why Look at Animals?” About Looking. New York: Pantheon, 1990, p. 1-26.

Brower, Matthew. “Take Only Photographs: Animal Photography's Construction of Nature Love.” Invisible Culture: An Electronic Journal for Visual Culture. Issue 9 (2005): http://www.rochester.edu/in_visible_culture/Issue_9/brower.html

Cosslett, Tess. “Child's Place in Nature: Talking Animals in Victorian Children's Fiction.” Nineteenth- Century Contexts, Dec 2001, Vol. 23 Issue 4.

Knoepflmacher, U.C, and Tennyson, G.B.“Introduction.” Nature and the Victorian Imagination. Knoepflmacher and Tennyson, eds. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press,

1977, xvii-xxiii.

Ritvo, Harriet. “Our Animal Cousins.” Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, Spring2004, Vol. 15 Issue 1, p. 48-68.

Watkins, David. “Victorians' festive fowl.” Poultry World, Dec 2005, Vol. 159, Issue 12, p. 23.

University of Saskatchewan Archives, Mary Taylor Postcard Collection, MG 296. Finding Aid.