"Tawow" Welcome to Pow-Wow Country!

Author: Patricia Deiter

Pow-wow to the First Nations people of Saskatchewan is a way of life and a symbol of cultural survival. We have more Pow-wows here in Saskatchewan on an annual basis than any other province or state in North America. Saskatchewan Pow-wows can be labeled as the best in North America as our dancers and drum groups are proven champions throughout North America. This dance form is traced to the Omaha and Pawnee people of the southern United States and came north through the Dakota people. In their honour, the Plains Cree refer to the dance as the Pwatsimowin or the Dakota dance.1

The term Pow-wow was used in the historical records for Saskatchewan by Church missionaries lobbying to have Pow-wows banned by the federal government as early as 1903. A history of Pow-wows in Saskatchewan reflects the struggles that confronted First Nations to retain their traditions and spiritual beliefs. Today, Pow-wows have become a source of identity for First Nations and a school for our children to begin to learn their Indian heritage.

The History of Pow-Wows

The 1876 Indian Act set laws and policies that were directed towards the assimilation of Indian people. The spiritual gatherings of Indian people in the west were targeted by the government from1884 to 1951 to not only assimilate First Nations but to also detribalize First Nations. The Indian Act of 1884 set the stage to prohibit the Potlatch ceremonies for First Nations in the west coast. This provision was expanded in 1895 to include Indian dances and ceremonies in which gift giving was practiced. The 1895 amendment to the Indian Act read:

The ceremonies were banned by government as they recognized that the ceremonies were connected to all aspects of Indian life and that the ceremonies undermined their assimilation policy. Church leaders vehemently opposed Indian spiritual beliefs, ceremonies and dances. Indian farm instructors argued that time spent away from farming was costly; while Indian agents argued that the costs associated with gift giving and the making of regalia was too much for an impoverished people. A main concern on the prairies centered on the Sundance, the major spiritual ceremony for the Plains people. The Sundance ceremony is the most sacred of plains ceremony and was the main ritual in which prayers would bring life. The Pow-wow is a more secular dance but just as loved by the people as it is a gift from the spirits that brings happiness to their communities.

The campaign to suppress all forms of Indian dancing in Saskatchewan was taken up with a vengeance by the infamous Father Hugonard, principal of the Qu’Appelle Indian Industrial School. In 1903 he wrote the first of many letters to the Indian commissioner expressing his disapproval of Pow-wows.3 Hugonard recorded that he saw Pow-wows as "the hotbed of Indian ways, laziness, and discord, and he recommended that Indian agents refuse all favors to known dancers."4 The Father’s stated concern was that his graduates were returning to their communities and returning to their traditional practices.

In answer to the campaign of Father Hugonard, Indian leaders, from Pheasant Rump and Striped Blankets (Ocean Man) band, petitioned the government to allow them to hold their dances just as white people enjoy their dancing.5 Indian Affairs Inspector William Graham believed that to allow the Indians to hold Pow-wows would be to stall their progress towards assimilation. Graham wrote to Indian agents in Saskatchewan that they should not tolerate Pow-wows on their reserves.6

Despite threats from government, First Nations continued to practice their traditional ceremonies. Many attended the dances that would be held in secret. Some Indian agents were supportive of the ceremonies providing that the events did not include the prohibited "giving away" or piercing referred to in the 1895 amendment. The Indian Agent for the Moose Mountain Agency was chastised for not enforcing a total ban on Indian dances by Inspector William Graham7

First Nations also adapted their ceremonies to accommodate the concerns of the Indian department. Whitebear, Pheasant Rump and Striped Blanket bands agreed to not give away, or consume the sacrificial dogmeat if permission could be granted to hold their dances.8 Others agreed to shorten the length of the ceremonies to be similar to the European Canadians days of rest on weekends and holidays.

Chief Thunderchild pressured to retain the dances based on Treaty negotiations.

He stated that he was assured by the Treaty 6 negotiator that they would be allowed to continue their dances.9 In 1911, a delegation of elders present at the signing of Treaty 4 traveled to Ottawa to discuss Treaty violations and to address their concern that Treaty did not prohibit their traditional ceremonies. They were assured that they could practice their ceremonies as long as they did not practice Giving aways or the mutilations. The official clarification of Section 114 for these elders gave rise to increased number of open ceremonies much to the dismay of the local officials and missionaries.10

By 1913, Father Hugonard reported the dancing at fairs and celebrations had increased on all reserves with the exception at File Hills and Oak Lake. Pow-wows were popular tourist attraction for white communities at local fairs and parades.

Pow-wows found support with various exhibition associations. Regina, Saskatoon and Prince Albert associations supported Indian villages as part of their exhibitions which combined with the Calgary Stampede, Brandon and Winnipeg fairs encouraged First Nations people to continue Pow-wows.

While the government withheld rations to known dancers, the Pow-wow organizers distributed rations to Indian camps and paid Indian people to put up their tipis at the fair grounds. They also held competitions for the best traditional dress.11

Through these efforts, Indian crafts such as beading, tanning of hides, and the making of traditional clothing were promoted and preserved through generations.

Archival photos indicate Pow-wows held at various exhibitions with one of the earliest occurring in Yorkton in 1908. Once again the Department of Indian Affairs attempted to suppress Indian dances for tourism with legislation. Section 149 of the Indian Act was amended in 1914 to read:

In 1915 Father Hugonard lobbied the Indian Department to complain that Inspector Graham obviously did not have enough power to stop the Pow-wow since all of the reserves in the south were still holding Pow-wows. Hugonard’s request was granted by Duncan Scott, the Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs in August 1915, when a circular letter was sent out to all Indian agents instructing them as follows:

Following the 1914 amendment and the policy circular, Indian ceremonies and

Pow-wows were suppressed on the prairies by withholding food in the form of rations, arrests, and police intimidation used to halt Indian dancing. Indian people responded by sending petitions, organizing political forums, adapting ceremonies into shorter time frames, and also resorting to use of Canadian courts and the outright disregard of the law to continue their spiritual practices.

The persistence of Indian dances and ceremonies throughout this period is a testament to the strength of First Nations ability to survive and adapt. Today, special mention is made at Pow-wows for the Standing Buffalo Dakota Nation and Thunderchild First Nations who both managed to continue to host Pow-wows for more than 75 years despite the government’s overt attempt to ban First Nations’ dances.

The Second World War influenced Pow-wows in a significant way. First Nations in Saskatchewan enlisted in the Canadian army in great numbers. When they returned home, they demanded freedom of religion and the right to practice their traditional ceremonies and dance. The post-1945 the Indian contribution to the war elevated Indian policy to the public. Veteran organizations, churches, and citizens groups across the country call for a Royal commission to investigate Indian life. Parliament established a Special Joint Committee of the Senate and House of Commons to hear various reports on Indian life. In the end, the Joint commission recommended to continue to an assimilation policy for Indian people but to reduce the overt oppression contained in the Indian Act. The result was the Indian Act in 1951 that allowed First Nations to continue their traditional ceremonies including Pow-wows14.

By the 1950s the overall effect of the Indian Act legislation and policies of assimilation and detribalization had made an impact on the ceremonial life for First Nations. Indian children because of the Indian residential schools were ashamed to participate and Indian elders were afraid to share and promote their traditional knowledge. Some of the rituals themselves were discontinued or altered but the Pow-wow endured and became even further enriched to include community giveaways and honouring, and fulfilling other ceremonial functions. The impoverished condition of reserves encouraged First Nations to continue to seek the support of non-Indians to host Pow-wows at exhibitions and local fairs.

The Pow-wows sponsored by the exhibition associations played an important role in promoting dancing. Photographs indicate Indian camps at the following exhibitions: Saskatoon in 1943 and again in 1958; and Yorkton in 1958.

First Nations looked with great enthusiasm towards camping at the exhibitions.

During the 1960s Pow-wows became increasingly popular events during the summer months on reserves. One factor that promoted Pow-wows came from the United States and the oil money that allowed the American reservations just across the border to host major celebrations. Reservations like Fort Peck hosted two or three major Pow-wows annually which in turn drew Canadian Indians across the borders to participate and compete in their Pow-wows.

The Contemporary Pow-Wows

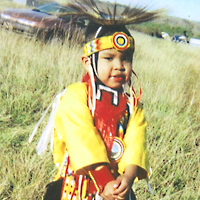

Contemporary Pow-wows are either traditional or competition pow-wows. The traditional forms are held on reserves and lack the competition programs for dancing and drum groups. Contemporary pow-wows include competitions which encourages high quality dancing and superb regalia. Champion dancers have to be fine athletes and also have the support of craftspeople to make their beadwork, feather work, and other material needs to compose traditional dance outfits. Today, dancers and singers compete for cash prizes that allow some dancers to become professional Pow-wow people. These professionals earned their living from dance competitions and from the making of Pow-wow regalia.

Pow-wows celebrate the circle of life by bringing our communities together to sing, dance, and renew kinship bonds and friendships. The dancers form the center of the circle, with drum groups around them forming another circle, with the audience as the next circle.

Each session of dancing begins with a Grand Entry, a processional of all the dancers and dignitaries of the community. The dancers enter the circle, grouped by age and dance style. The national flags are carried in by the lead dancers. First Nations’ veterans and dignitaries follow the flag and led the grand entry procession. The Grand entry is followed by a prayer and a Flag song to honour our nations. The next song is a Victory song which reflects pride in our cultural survival.

Inter-tribal dancing forms the core of the Pow-wow celebration. All the dancers, regardless of age or categories enjoy the intertribal songs as they dance in harmony.

The dancers all wear their own unique outfits, which are made by themselves or by friends and relatives. A dancer’s Indian name or spirit helpers may appear on designs. The Pow-wow outfit is considered sacred and brings honor to the spirit world, the dancer, their family and their tribal community. Dance Competitions and specials, in the form of give-aways or special contests complete the Pow-wow program. The Competitions are a crowd favorite as dancers are judged for their rhythm, foot work, endurance, and style.

One aspect of Pow-wow that cannot be overlooked is that honouring of the First Nations veterans. Veterans carry flags in Grand Entry, retrieve eagle feathers and to provide prayers throughout the event. The honour displayed to the veteran is a reflection of our value placed on people who provide a service to people. The Veterans and their willingness to give their life in the service of others merit our highest respect. This honouring of the veteran is also an old tradition for the plains people who have a warrior tradition.

The drum is referred to the heartbeat of our nation. The drumsticks connect the spirit of drum and with the spirit of the singers. Many of the drums used at pow-wows have been handed down within families or given to a drum group. Most of the drums have been ceremonially blessed and must be smudged and prayed over before being used.

The drum also refers to the singing group which may consist of any where from four to twenty singers. Many singing groups have sung together for a number of years and have an established reputation. Pow-wow committees usually extend an open invitation to singing groups and are honoured when a large number of groups respond. Throughout the Pow-wow a variety of different types of songs are heard depending on the event.

Drum groups are required to sing Honour songs, Flag songs, intertribal songs, competition songs that are unique for each group, and round dance songs. The songs differ in tempo and words but they all follow a similar structure. Some songs may be very old past through generations and others are recent compositions. The singers depend on their lead singer to set the tempo and melody for the song. Lead singers are greatly appreciated as they rely solely on memory for the variety of songs that they will sing at Pow-wows. All songs have a copyright. That is they cannot be recorded and then sung publicly by another drum group. There are traditional protocols to observe in transferring songs.

Pow-wow include many honourings by community members known as Give-aways or specials. The Celebration could include events such as a hoop dance but the core is the intertribal dancing and competitions. Once the competitions have concluded, the flags are danced out and thus ends the pow-wow for the day.

The dance style and regalia of the contemporary Pow-wows have their origins in the ceremonies and warrior societies of the Plains tribal groups. Some styles, such as the Women’s Jingle dance, are recent additions to our northern Pow-wows but have become a part of this continuing tradition.

The dancer’s regalia reflect standards established for each category and also reflect the dancer’s tribal group and individual beliefs. All the outfits are handmade and are considered as ceremonial regalia. Dancers are not free to lend out their regalia and nor should their outfits be handled by spectators.

Some of our dancers will wear geometric designs common to Plains people while others will have floral patterns embedded in the outfits to reflect their woodlands background. Many dancers use modern materials to construct their regalia such as sequins, glass beads, and colored fluffs, but the style is distinctively Indian.

Men’s Traditional- Original and Contemporary

The men’s traditional dance stems from the days when hunting and war parties upon returning to their home village would celebrate their success by recounting their encounters with the prey or enemy by re-enacting them through dance.

The regalia worn in the men’s traditional style is highly symbolic and the colours are more subdued that those worn in other men’s dance styles. The traditional dancers wear a single bustle, which is made of eagle feathers.

First Nation Pow Wow - Beardy's and Okemasis Nation International Pow-Wow, August 24-26, 2001 (image details) |

The bustle is representative of the battle field and its circular shape is symbolic of the cycles of nature and the unity which exists among all things.

Most men dancers wear a headdress called a roach. These roaches are made from the hair of a porcupine and vary in size according to the category. The men’s traditional dance roach is long and often topped with two eagle feathers that signify enemies meeting in battle. The dancers usually carry items that denote their status as warriors such as a shield, coup stick (which is used to challenge the enemy and is decorated with eagle feathers representing achievements earned in battle) and an eagle wing fan. Their regalia could also include the following: beaded breech cloth, cloth leggings, breastplate, chokers, necklaces, feathered or animal headdresses, pipe bags, war clubs, shields, beaded cuffs, eagle feather fans, bells and miscellaneous other parts.

Each dancer relates his story of a hunter stalking game or a reenactment of a battle. The dancers will frequently turn their head from side to side in search of their game or enemy. Frequently, the men’s competition will include a Shake and stomp dance. The shake dance has a fast steady beat in which the dancers are to imitate the actions of a prairie chicken, moving their muscles and body in time with the music.

The Men’s traditional dance has two styles: contemporary and traditional. The traditional outfit is more subdued with more subdued movement. The contemporary style dancer is flashier in coloring and more active in movement.

Men’s Grass

During this century the grass dance has been the most dominant of men’s dance styles in the Northern plains. This style of dance was introduced into the Northern Plains and promoted by the Dakota who purchased, from their Omaha relatives, the right to organize grass dance societies and execute the ceremonial dances of the society. Membership in the Omaha Society, as it is called by the Dakota was extended only to the most accomplished warriors who wore braids of grass tucked in their belts during the society dances thus giving rise to the name grass dance.

The Plains Cree used this grass dance to demonstrate the men’s ability to control their muscle movement to song. This style of dance is known as the traditional Grass dance style and is distinctive as the dancers rely on body movement not foot work to demonstrate their skill as a dancer.

The most distinctive feature of male grass dancers is their long flowing fringed outfits that vary in style and color. Their regalia are without the feathered bustles and miscellaneous adornments of other male dancers’ outfits. The longer-haired porcupine roaches with eagle feather stripped except for the tuft, color-coordinated beaded headbands with circular rosettes, beaded chokers, beaded wide belts with side drops, beaded moccasins, heavier bells, apron breechcloths and leggings fringed with horse hair distinguish the outfits worn by the grass dancers.

The style of grass dancers is comprised of easy flowing body movements of rises, falls and turns, imitating the motions of eagles and other graceful birds. The controlled use of intricate and shuffling footwork, arm and head movements and a variety of combination are also typical to grass dancers. Those dancing this style characteristically shake their shoulders, sway their torso from the hips in a side to side motion, dart suddenly changing their direction, and employ a series of trick steps, giving them the appearance of being off balance and resembling the grass blowing in the wind. The dancers keep their heads moving up and down in beat with the drum or give a quick nod with each beat to keep their roach feathers moving, which is a sign of a good dancer.

Men’s Fancy Dance

There are two stories of origin for the men’s fancy dance. A champion fancy dancer from North Dakota once explained the origin of the fancy dance as arising from a ceremony in which a man was so grateful to that ceremony and the drum style that was used to doctor his loved one that he made a special outfit and dance to honour this way of prayer. The ceremony used the fast beat of a water drum and the dancers are to coordinate their feet and body work to move as fast as the drum. The brightly colored feathers of the original ceremony are also reflected in the bright vivid feather bustles of the men’s fancy dancers.

Another story traces the men’s fancy style of dance to the Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show days of the late 1800’s that operated in the northern United States. The war dance performers were asked to wear two bustles and to make their regalia more colourful. They were also encouraged to jazz up their steps and movements. The modern fancy dancer was only recently introduced to the prairies during the late 1950’s, coming from the tribal groups in Oklahoma.

The men’s fancy dance incorporates acrobatics, spinning, and speed with the standard double steps and movements of the grass dance style making it a very challenging dance style. The dancers execute fancy footwork and an array of complex moves while keeping beat with the drum and in competition must stop with both feet on the ground or in a split precisely when the drum stops. Trick songs, with unpredictable stops, are often sung for men’s fancy dance competitions and exhibitions. This dance is also a test of endurance that warrants great muscle control. The dance is extremely vigorous demanding perfect rhythm, coordination and strength.

Prairie Chicken Dancers

The Prairie Chicken dance has been influenced from both the Plains peoples’ warrior societies and the Plains Cree Prairie Chicken ceremony. The dance is distinctive in style of bustle which is made from with prairie chicken feathers. These dancers also often carry mirrors that remind us of the role of scouts during the pre-reserve period when mirrors were used to communicate during times of war or hunting. These dancers imitate the movements of a prairie chicken when dancing. The dancer’s artistry should reflect the warrior’s spirit to become one with his surroundings when in battle or scouting. He should be so careful in his movement and actions, that his enemies would mistake him for a prairie chicken.

Women’s Traditional-Stationary and Walk About

In the past women only danced on the sidelines in support of the male dancers unless songs were sung specifically for them to come out into the centre to dance. Their styles of dance were very modest and dignified, the most common being the stationary, the graceful walk, and the side step. It was not until the evolution of the contemporary pow wow, in the 1950’s, that women came out to dance along side the men in intertribal dancing. The women’s traditional style of dance carries forward the dance traditions of women and is either done stationary or in the manner of the graceful walk.

When dancing stationary the women remain in one place bending their knees slightly and moving their bodies subtly up and down in beat with the drum while slowly moving their feet to make a discreet turn in one direction and then the other, symbolically, seeking the return of their warriors. Those dancing the graceful walk take discreet steps in beat with the drum.

The stylized walk is a forward "two tap shuffle steps" with the body posture held erect and body bobbing up and down, bending lightly at the knees in time to the rhythm while moving their bodies slightly from side to side while the body posture remains erect. One hand is usually on the hip and the other carrying a shawl.

The women raise their fans when the honour beats are rendered. The symbolism associated with this act varies in First Nations. For some, only those who have lost a son, brother, or husband in battle who may raise their fan and it symbolizes their unending quest for their return. Other use the fan to honour the eagle, a symbol for the Indian way of life. They raise their eagle fans in the honour beats to honour this way of life.

The women’s traditional dancers wear long fringed buckskin dresses with solidly beaded yokes, matching wide beaded belts, braid wrappings, knee high beaded moccasins called "high tops"; long fringed shawls complete the beauty of the outfits.

Women’s Jingle Dress—Original and Contemporary

First Nation Pow-Wow - Beardy's and Okemasis Nation International Pow-Wow, August 24-26, 2001 (image details) |

This style of women’s dance is believed to have originated in the Mille Lacs, Minnesota area where it is said that an Anishnabe man dreamt of women wearing dresses adorned with tin lids cut in a fashion so they would jingle. The tin used to make the jingle cones are made from tobacco lids. Tobacco is considered sacred and used for prayer and therefore this dance dress is considered as sacred.

In the vision given to Anishnabe people, these dresses were to be used for doctoring and specific songs are used for the Jingle dance. It is recorded that the people of White Earth in the 1920’s gave the jingle dress to the Dakota who promoted this style of dance in Pow-wows. Following the introduction of the Women’s fancy shawl style of dance, the popularity of the jingle dress style began to decrease and all but died out until the early 1980’s when it was reintroduced.

Today there are two forms of Jingle dancing: contemporary and original style. In contemporary, the women carry fans which they raise during the honour beats of a song and their steps are similar to the women’s fancy dance steps. In the original style, the women’s foot work is closer to the floor and their outfits are characterized by a lack of fans or feathers.

Women’s Fancy Shawl

Plains Cree women before 1960 wore beaded capes made of velvet and danced in fast steps that seemed to hover just above the ground. Influence from the United states in the 1960s gave rise to a new style that was added fancy footwork, spins, and the use of shawls. The dance requires agility, strength and endurance. One of our champion dancers noted that she honours the butterflies in her dance movement.

Today, the women’s fancy dancers typically wear multicolored cloth dresses with satin ribbon edgings. Matching beaded yokes, beaded wide belts and "high top" moccasins complete their outfits. The female fancy dancers also wear feathered hair pieces, "designer" shawls with long multicolored fringes to enhance the overall color coordination and beauty of the outfits.

The contemporary women fancy dancers’ style of dancing is similar to the male fancy dancers’ vigorous turns, whirls, changes in body positions and intricate footwork but are executed on a smaller scale and without the acrobatic variations. The drum beat used for their competition is often slower than that used for the men’ fancy dance but only the skilled can keep in step with the fast beat. Footwork is the chief element of the women’s fancy dance.

Closing Comments

Today, Pow-wow dancers are considered contemporary warriors, who are the survivors of a war that has been won in terms of retaining an Indian way of life. To be a Pow-wow participant is to honour the struggle of our ancestors and their desire to preserve Indian cultural ways. The Pow-wow is Indian and, as long as it continues, we as Indian people will continue.

Bibliography

Deiter-McArthur, Pat. Dances of the Northern Plains. Saskatoon: Saskatchewan Indian Cultural Center, 1987.

Leslie, John and Ron Macquire. The Historical Development of the Indian Act for Department of Indian Affairs, 2nd edition, 1979.

Mandelbaum, David. The Plains Cree: Ethnographic, Historical and Comparative Study (Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center, 1979) 218.

Pettipas, Katherine. Severing the Ties that Bind Government Repression of Indigenous Religious Ceremonies on the Prairies. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1994.

Powers, William K. War Dance Plains Indian Musical Performance. Tucson & London: University of Arizona Press, 1990.

Tobias, John L. Protection, Civilization, Assimilation: An Outline History of Canadian Indian Policy. Western Canadian Journal of Anthropology 6, no. 2 9. 1976 .

National Archive of Canada, Department of Indian Affairs RG 10 collection.

Notes

1. Mandelbaum, David. The Plains Cree: Ethnographic, Historical and Comparative Study (Regina: Canadian Plains Research Center, 1979) 218.back

2. 1895 Indian Act Amendment to Section 114 (c.35, 58-59 Vict.) Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, Indian Acts and Amendments, 1868-1950 (Ottawa: DIAND, 1981), 95-96.back

3. Pettipas, Katherine. Severing the Ties that Bind Government Repression of Indigenous Religious Ceremonies on the Prairies. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1994, 103.back

4. Hugonard to the Indian Commissioner, November 23, 1903 (NAC RG10, vol. 3085, file 60,511-1) back

5. Petition to the Indian Commissioner, Department of Indian Affairs, from the Indians from the WhiteBear, Pheasant Rump and Stripe Blanket Bands. January 1909 (NAC, RG10, vol. 3825, file 60,511-2). back

6. William Graham, Inspector of Indian Agencies (NAC RG10, vol. 3825, file 60,511-2). back

7. W. Graham to the Secretary of Indian Affairs, August 7, 1914 (NAC RG 10, vol. 3865, file 60,511-3). back

8. T. Cory to Secretary Indian Affairs, March 13, 1909 (NAC RG 10, vol. 3,825, file 60,511-3); also Whitebear band members to Indian Affairs Department February 4, 1926 (NAC RG10, vol.3827, file 60,511-48). back

9. Pettipaw, 129 also Chief Thunderchild to Department of Indian Affairs, June 4, 1914 (NAC RG10, vol.3,825, file 60,511-4, part 1).back

12. Pettipaw, 149 also "An Act to Amend the Indian Act" S.C.1914, c.35, 4-5 George V in Indian Acts and Amendments, 1868-1950,132. back

13. Duncan Scott to Agents and Inspectors, August 19, 1915 (RG10, Volume 3826, file 60,51101 part 1). back

14. Tobias, John L. Protection, Civilization, Assimilation: An Outline History of Canadian Indian Policy. Western Canadian Journal of Anthropology 6, no. 2 9. 1976. back